I.

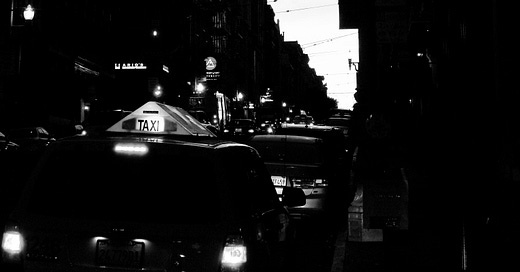

Years ago—and the antiquated, pre-smartphone, character of this anecdote will become clear—I had a friend who couldn’t hail a taxi. Regardless of how he contorted his arm, a blur of yellow taxis would speed past, all of them, it seemed, with empty back seats. Most people in New York could have spotted his problem at a glance, yet he remained implacable. He was short, almost twitchy in his movements, and I tried to explain that appearance wasn’t the problem—yet he insisted that drivers perceived him as angry, dangerous, somehow foul-smelling, that his suits must look counterfeit, and this triggered a grumbling, annoyed tone that lingered in the air whenever we finally jumped into a taxi that I would flag down. The driver, he assumed, was vindictive, judgmental in his perceptions like all drivers; at the same time the driver perceived this young passenger in a wrinkled suit as an entitled, arrogant man, unnecessarily rude, which I must admit was a reasonable and mostly accurate conclusion.

I hope that it is sufficiently clear that I’m working to fashion myself as the omniscient and kindly figure in this story—the only person in the taxi with awareness of every perspective. Because my friend couldn’t quite figure out that I never hailed taxis from the same spot he picked, that I always moved toward a location that was more conducive to the eyeline of a driver, in the direction of traffic, with room to stop. This wasn’t complicated, nor did it demand much thought beyond a straightforward, instinctive calculation about a driver’s perspective while you stand with a stretched arm on the curb. At the same time, I assume that some drivers formed longterm conclusions about my friend’s character based on the harshness of his tone. I see the lift of eyebrows in the rearview mirror—the slight condescension, the perception that this is a solidified personality, rather than a flash of annoyance.

Jumping ahead a few years to another gust of memory, I recall a different friend, thoughtful, clever, at a table for two in a restaurant in Brooklyn, when a server tosses two plates onto our table with the delicacy of a sanitation worker tossing bottles into a dump truck at dawn. Jolted, my friend flinches, unsure of the cause, and she complains, though that complaint is delivered in a whisper and is intended exclusively for my ears. Had the server felt slighted? What was her problem? Is she purposefully rude? In my ongoing struggle to appear benevolent in these paragraphs, always empathetic in the reader’s eye, I’ll mention that we didn’t know the full story, that our server might have just heard something horrendous, that something might be affecting and distracting her day for which we would have sympathy, that her behavior is almost certainly less about our day and more about her day.

Of course it is solipsistic to presume that what surrounds you involves you. This is an infantile perspective, the world as seen through the bars of a crib. Some people are rude in general rather than rude in particular. Conversely, a kind word from a stranger might not be about you—it isn’t necessarily flirty, or directed, but just someone’s personality. It will always be tricky to know what’s particular and what’s general.

Yet I also know that I can’t ever escape my perceptions, my interpretations, and that my instinct, often, is that I’ve affected the environment, that I’ve prompted the behavior that I witness. In the end the only truth that I possess is my sensations, though it is easy to forget how fallible they are in guiding me through life. If I observe a car accident, I will observe a different accident than a man who stands right next to me—although I’m not always certain what to do with this conclusion in my life. I want to be faithful to my perceptions, yet also recognize how fallible, misleading, and simply unreliable those perceptions are when I move through the world.

I was on a train last year when an older woman boarded and plopped down in front of me—taking the final empty seat in the carriage. After the train jerked forward and moved away from the station, a ticket collector strolled down the aisle and asked for her ticket, for which she expressed outrage, horror, dismissal. You’re only going to ask me? I admire her gall, however foolish it made her look. From her perspective, it seems perfectly reasonable, as she saw the ticket collector stroll past rows of passengers without a single word until he reached her seat. But if her perspective could have included just a few minutes before she boarded, she would have witnessed that same ticket collector questioning everyone in the carriage.

II.

The very best artists, to my eye, capture these moments of perception, these moments when an individual sensibility meets the larger world, these moments when the particular, distinctive gaze of a single person is revealed as essential to their character. We’re confined to the world of our perspectives, however faulty, yes, and when you peer at a grand canvas or feel enchanted by a novel, you’re absorbing the sensations of the artist—these are intimate, captivating moments, where an artist holds your hand and reveals what they see.

Writing well, in particular, requires excavating what’s intrinsic to you and then figuring out how to toss that individuality onto the page. The manner of expression, the way a sentence builds, accelerates, the weight of the words, all of it reflects the sensibility of the writer. Whether I am able to craft sentences in an effective way isn’t for me to decide, but I can affirm that I’ve done plenty of digging, that I’ve torn apart sentences for decades and looked for structures and strained to identify a voice that feels true and vibrant and essential—ideally, what emerges is shaped by my perspective of the world.

Despite my best efforts, I’m aware that what I express on the page will still appear, for some very misguided and unfortunate readers, in a way that’s contrary to my intentions. When you’re trying to express your perspective in the world, this confusion, as every infant experiences, is both maddening and guaranteed. Language is messy, and you can’t predict how others will interpret your words. All you can do, as a person, as a writer, is capture your sensations and articulate them to the best of your abilities—how they’re perceived isn’t under your control.

III.

Over time I’ve discovered that the em dash works well in my writing and helps to capture the voice that I want. It provides a pause, a hiccup, a chance to dance around a point without losing the beat; it steers a sentence in a way that’s unique, unlike a semicolon, which I use less frequently, and a comma, which dot my sentences, I’m aware, like I’m a pointillist painter.

Obviously I’m not the first person to use em dashes, but I’d like to believe that I use them in a way that’s conducive to my voice. I began using them about ten or fifteen years ago, and they’ve solidified into a tool that I use in both formal and informal writing. If you examine my writing—which I insist that you do—you’ll find that I use em dashes in precise situations, that there’s less puffery than it might appear, because I mostly use them to adjust the speed with which I deliver the information that I’m attempting to convey. When I write a sentence, it’s a rare day indeed that the speed of my sensations matches the speed of composition; what it feels like, instead, is a bumbling, expansive multitude, where too many ideas bubble to the surface at the same time, but an em dash, for me at least, provides one way of controlling the pace.

Unfortunately, it has recently come to my attention that em dashes are one way in which writing is perceived as algorithmically generated. My first response to this knowledge is to point out that our smartest computers, our most advanced generators of language, have stumbled upon the very manner of writing that I find effective. Just linger on that point of agreement, between our computer overlords and my sense of style, for a moment before you reach my second response, which is a bit closer to apprehension, because I’ve learned that em dashes, for some people, now result in automatic dismissals, automatic perceptions of forgery.

In some ways this is a perversity of the Turing test. The original test highlighted whether a computer could fool a human into believing that it was human. I’m placed, conversely, in the paradoxical situation of attempting to prove that I’m not a computer—which, I might add, is probably something that we’ll all end up doing more and more over the coming years. Perhaps this is a bit like trying to prove that you’re conscious. You’ll find that this is also difficult, regardless of how you approach the problem, because the only truth you possess is your own sensations, your own consciousness, your own perceptions.

So now I’m left in the peculiar position of knowing that the way I express myself is considered a way to detect algorithmic writing. Do I change my style so that I appear less like a computer? That seems rather backwards. Technology has certainly gone in the wrong direction if that’s the solution. I want to avoid erroneous conclusions, I don’t want people to misperceive my writing, but what was once a stylistic habit, a marker of my identity—the use of em dashes—has become a mark of inauthenticity. To abandon the style that feels most true to my perceptions, simply to appear less like a machine, to avoid misperception by others, does feel like a mistake that could only be made by a human.

But what you write is so unique in every way that mistaking it for AI should be a crime. I doubt AI use the em dash for rhythm, and even if it does it won't be as beautifully done as what you write.

I think of you as the writer of clear thinking, of the one different perspective, the one that seems similar to others, but is written from the slightly different angle that reveals a truth unearthed by anyone else. Your sentences are to me like rivers, or glass prisms, so clear, translucent, precise, breaking the light into colours.

There's no doubt for me about what is written by a robot and what by Charles Schifano.

I had NO clue about the em dash as a potential identifying characteristic of AI. Also, I admire the way twine the sinew of personal anecdote with the muscle of your main point - it's seamless.