Every day comes with idiocy. If you’re even halfway awake, it will surely hit you—the perpetual assault of idiocy, the tornado of idiocy, the hour-by-hour reminder of idiocy in every news report and overheard conversation and peculiar behavior by the stranger across the street, all of it incalculable, overwhelming, impossible to track and impossible to sift through, so that you never really know what’s the worst, the grandest, the largest idiocy of all, until something so pungent comes along that it shoves the competition aside and declares itself the clear winner:

We're not going to show the full statue of David to kindergartners. We're not going to show him to second graders. Showing the entire statue of David is appropriate at some age. We're going to figure out when that is.

This comes from the wonderfully named Barney Bishop III—who sounds like he stepped right from a P. G. Wodehouse novel so that he can step on a rake and smack himself in the face. In one delicious interview, Barney Bishop manages to be fiery, confused, petulant, childish, show distain for teachers, show distain for parents, show distain for the entire state of New York, contradict himself, contradict himself again, and speak, the entire time, like a hilariously-exaggerated cartoon version of how the left perceives the right to speak. It is a sight to behold.

Normally I refrain from such direct criticism. Ideas aren’t people, and I am a strong proponent of ruthlessly attacking ideas while seeing individuals as pretty much unrelated to the ideas that they espouse. And this basic principle probably comes from my background in art and writing, where, if you have any hope whatsoever of improving, you need to put your work into the crucible—to hear its flaws and missteps and follies—without identifying yourself with your art. If you find yourself shivering in the first moment of hearing criticism about something that you created, you might want to consider leaving the writing class, or stepping outside the art studio. Believing that statements about your art are statements about you is quite clearly not a good place to begin; nearly all criticism says more about the critic than about the subject—so the artist needs to decide what’s valuable without insecurity. Criticism is just information, either useful or not, and criticism of your art might say something about the noun art and nothing at all about the possessive adjective your.

You also won’t find in the thousands of pages of my public writing, I’m fairly sure, a single example of a personal attack. Not only does it go against my general ethic of focusing on ideas rather than people, but it is typically a boring style of writing: the hot-take political essay that is slowly filling up the entire world’s servers and driving the semiconductor industry to work faster and faster to keep pumping up the processing power so that there can be more diatribes by the most politically engaged and least politically aware. (That is, incidentally, a type of writing that I’m mentioning, and not a specific person.) Even when I do write negative reviews, I strive to understand what the writer has attempted, to concentrate on the writer’s objective, to assess the work based on sincere criteria that fits the art, rather than simply my own inclinations and tastes.

Why the exception for Barney Bishop III, my current favorite comic figure in American life? It is first hard to ignore that Bishop is so incredibly outrageous that being indirect would be like casually alluding to the cockroach in the corner of the room. He is a very angry man, he is very clearly furious with the people who disagree with him, and he has very specific stereotypes for large groups of people—New Yorkers, journalists, the entire American public that lives outside of Florida. He bends himself into such contortions with his bombastic comments that I worry for his back. And I think that it would be inconsiderate of me to be subtle, to treat him as a member of a group rather than as an individual, to fail to meet his expectations of how he assumes his opponents think. So it is with a full measure of respect that I imbue the persona that satisfies the stereotypes that he has already chosen for me. You’re welcome, Barney Bishop III.

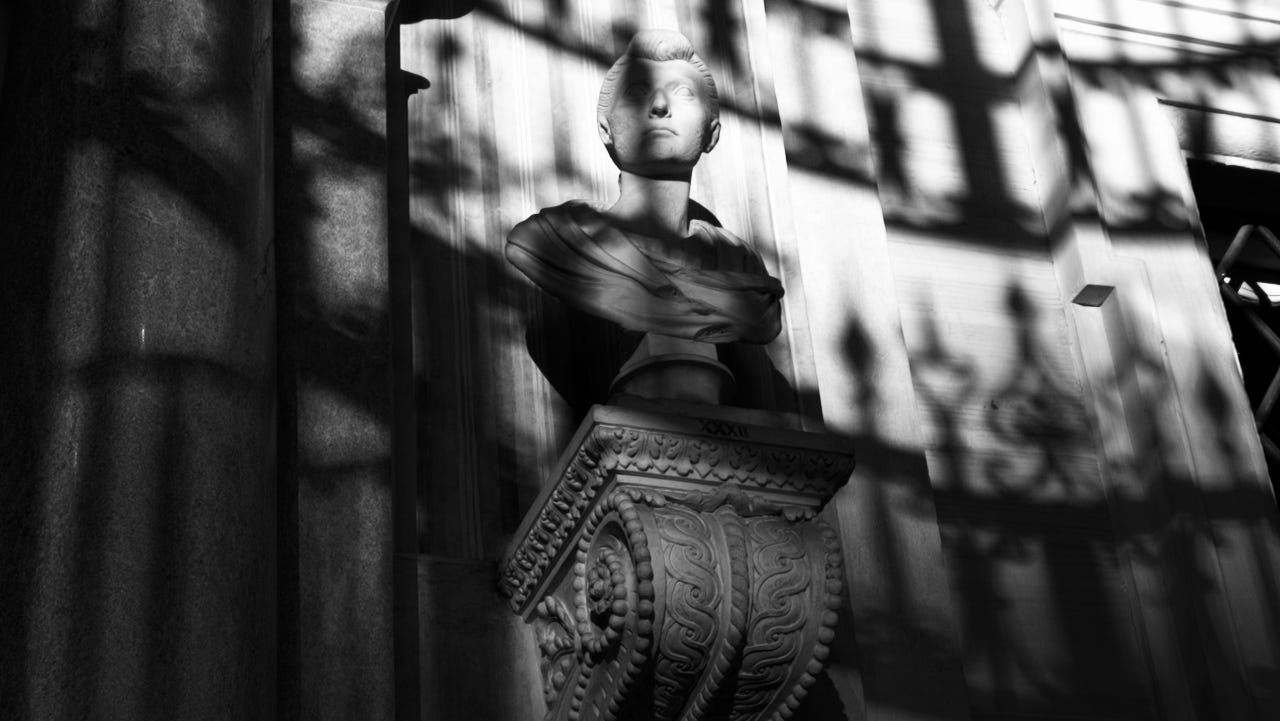

The issue here is fairly straightforward: whether Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni’s 16th Century statue of David is suitable for children. Principle Hope Carrasquilla of Tallahassee Classical School was told to resign—which is a genteel way of saying was fired—after a picture of the statue was shown in one class and a parent objected. There’s some controversy about whether the actual resignation was related to the statue or other issues, but that claim is easily tossed out of my courtroom, as Barney Bishop III betrays the truth and places his entire foot and most of his leg into his mouth with his statements about the statue.

If you want to defend David, a claim can be made about culture, history, the magnificence of art, creation, even religious allegory, but this particular case is actually much simpler: the image was shown in a sixth grade class about Renaissance art, and I have a difficult time envisioning any lesson about Renaissance art that doesn’t show David. Not showing that picture would be similar to removing the murder scene from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar because of the violence—you would still have the remaining play, yes, but what would that decapitation leave you with? A fair question is whether Tallahassee Classical School, with a curious and notable emphasis on the second word in that name, condescends to students by teaching them about the Renaissance while suppressing what is quite clearly the most notable Renaissance symbol?

David is seventeen feet, or five meters, and carved from what was, in fact, a timeworn slab of white marble. Before Michelangelo even picked up his chisel, several other artists had chipped away at the eighteen-foot block, which left it ragged and cracked, and, unfortunately, nearly forty years old. Yet Michelangelo spent three obsessive years laboring with the marble from Carrara to create the figure that’s now most representative of the Florentine Renaissance. It is worth remembering—and this part requires you to sit down—that the controversy about David’s nudity at Tallahassee Classical School involves a photograph, and, ridiculously, the photograph is of a sculpture.

You might notice, while looking in awe at the sculpture, that there’s a slight dichotomy to the pose, as David clearly stands as a pinnacle of beauty and grace and power, an ideal far beyond any reasonable expectation for normal humans who must work long hours and sleep in uncomfortable positions and who have bad backs and trouble digesting; yet it is also, simultaneously, human, or humanist, and chiseled into a pose that seems almost graspable by the lowly humans that stare upward. If you are teaching a child in Tallahassee Classical School, it might be worth pointing out that David straddles the line between the godlike and the human, because Michelangelo has carved something for us that shows a figure that’s both utopian yet somehow within reach, those two potent features of striving that were present in Florence during such a short but crucial period, when divine perfection came with a hint of hope—which might be one reason why this figure, of all the great Renaissance creations, symbolizes a period of rebirth in the world, when artists who were also scientists and engineers looked backward, to ancient Greece, to create something new.

You might notice, while looking in awe at the sculpture, that there’s another dichotomy in the pose. David is the strongest man that you’ve ever seen, but he’s also the most gentle man that you’ve ever seen, and Michelangelo sees no contradiction in this duality. To be potent and formidable and devastating doesn’t negate the ability to be fluid and gentle and beautiful. If you are teaching a child in Tallahassee Classical School, this is probably a good topic to discuss. David has a swagger, a certitude of purpose, an inward confidence, which comes from both the muscles that form his body and the elegance with which those muscles hold him upright. He’s contrapposto, standing on his right leg and looking left: defiant, fearless, bold.

You might notice, while looking in awe at the sculpture, that he is naked. How long it takes for you to notice this fact and how much this fact concentrates your thinking will almost certainly say more about you than about the sculpture. Just as nearly all art criticism says more about the critic than about the art, nearly all impressions of David say more about the viewer than about David; he’s standing, exposed, equanimous, the pinnacle of beauty, without shame. Nothing about his pose, however, betrays a knowledge of his nudity. Nothing differentiates his nose from his finger, or his knee from his penis—he is simply a body. Nothing present in the sculpture emphasizes the nudity: the viewer must decide to make that decision. And if you are teaching a child in Tallahassee Classical School, there’s no reason for you to take the complexes and biases that you have about the human body and consider them intrinsic to the sculpture.

You might notice, while looking in awe at the sculpture, that it is based on a biblical story. Michelangelo was driven by a religious impulse, and, in many ways, David could be described as the greatest work of Christian art, though I wouldn’t relegate such a universal symbol of man to just one tradition. Michelangelo was just too good of a sculptor. You don’t need any religious impulse or to be from any particular country to claim David—a symbol of impossible, godlike perfection, a symbol of human striving—as your own. Nevertheless, Michelangelo was pious, his sculpture was first commissioned to adorn a church, and he understood that he couldn’t sever any one aspect of the body: it required three years of constant work to ensure that every inch of the marble represented beauty and power and a striving humanity. For Michelangelo, for the pious man, how could he cover any portion of the creation that he didn’t believe was fully his? You would assume that his religious descendants would recognize that this idyllic image of David comes before the fall—and that any accompanying shame is exclusively theirs.

You might notice, while looking in awe at the sculpture, that he is fragile. In many ways the entire Florentine Renaissance was fragile, its very emergence based on contingencies, a mere consequence of just the right confluence of factors, striking in a particular spot at a particular time after centuries of toil and rot and substance living, with the apotheosis of art somehow, improbably, miraculously, emerging into this desperation. David, as the symbol of this period, enlivens and uplifts and enchants with his beauty, but that beauty is, as always the case, fragile, vulnerable, temporary. If you are teaching a child in Tallahassee Classical School, perhaps a discussion about fragility, about the impermanence of beauty, and life, would be worthwhile. The majestic qualities that came together in Florence for just a short time eventually dissipated, and the qualities that comprise David’s beauty are, too, temporary marks—viewers recognize this beauty as they stare upward yet they still sense that it is fleeting, and utterly human.

And perhaps nothing is more life-affirming than reminders of that fragility. Bodies tire, slow, and eventually wither, and any life-affirming ideal is worth grasping in a world that’s full of pain and all-too-certain heartache. There’s no Florence today, or widespread cultivation of an uplifting, striving spirit of individuals. What we have, instead, is a culture that promotes a mindset of seeing categories of people rather than individuals—the blathering stereotypes hacked up by Barney Bishop III is what David teaches you not to see. It is a culture that criticizes people rather than ideas, that treats people as representatives of groups rather than as individuals, that picks out all the idiocies of the day and forgets to look for charitable reasons for our human faults.

I want David shown to everyone, the sculpture is integral to history and culture and art and religion and it doesn’t matter where you live or when you were born for that to be true, and I also don’t want adults to teach children the biases they have about nudity that aren’t even present in the sculpture. To believe that David is shameful, embarrassing, has parts that need to be covered, is to say something about you and nothing at all about David—it also means that you’ve never actually looked at the sculpture. Of course the real paradox, for me at least, is that I certainly wouldn’t want anyone like Barney Bishop III near the classroom.

Last year, I finally made it to Florence, and stood in awe of Michelangelo’s David. The veins in his hand. Everything about it was breathtaking. As for the kerfuffle over the teacher’s forced resignation, Mr. Bishop indeed sounds defensive and angry. Although I’m not sure why the teacher told her students not to tell their parents about seeing the David photo. The world seems increasingly off kilter, and this destructive divisiveness and criticism of people over ideas is leading us to our ruin. Thanks for another thought provoking essay, Charles.

I very much appreciate your inference (or perhaps it's quite clear!) that Barney Bishop III is a right wing authoritarian who is matched by the authoritarians on the left. Categories, categories, categories. When it comes to art, my only crime is that I want all of it, from all angles. I also think it's quite astonishing that Renaissance Art is being taught to sixth graders.